CRITIQUE

Hard Rock Cafe Porto

The architecture of branding and the tourist city

Architect and FAUP PhD

© Carlos Machado e Moura

I.

Among global capitals — such as London or Paris —, financial centres — like Doha or Singapore -, gambling destinations — such as Las Vegas or Macau —, tax havens — such as the capital of the Cayman Islands or Panama City —, sunshine meccas — such as Cancun or Marbella, — cultural centres — like Florence or Krakow —, there are two things in common: mass tourism and a Hard Rock Cafe.

With 6.8 million visitors in 2016, and elected for the third time as “Best European Destination” in 2017, the city of Porto now has its own Hard Rock Cafe.

Born in 1971 in London and internationalized in 1982, owned by a Florida Native American tribe since 2007, the Hard Rock Cafe is today a global brand, with headquarters in Orlando. Its extensive portfolio includes a total of 191 establishments (cafés, hotels and casinos) in 54 different countries.

In Portugal, the first franchise of the brand opened in 2003, taking over the old Condes cinema in Lisbon, in a process that was quite controversial 1. In 2016, a new franchise of the group opened in the city of Porto.

The opening of the Hard Rock Cafe in Porto is a confirmation of the tourist “boom” of the city and the country. It also raises more questions about the shock between local and global culture, the conservation of historical heritage and its adaptation to market opportunities, the fusion between consumption and memory, the limits of the exploration and capitalization of culture, the weight of tourism on urban rehabilitation and the subjection of architecture to marketing.

II.

Attesting to the complexity of the process is the fact that several parties are involved: two clients (Hard Rock Cafe International and local promoters), two architecture studios (Hrynkiewicz & Sons Architects – HiS – and Floret Arquitectura) and three cities (Orlando, Gdansk and Porto).

The first stage involved the identification of a building to take in the space. To achieve this, the local promoters of the franchise, under supervision of Hard Rock Cafe International, contacted Floret Arquitectura, a studio with extensive experience in the rehabilitation of buildings in Porto. With the main requisites being a central and busy location and a historical veneer that corresponded to the touristic image of the city, the option selected turned out to be a 19th Century building located on the corner of Rua do Almada and Rua Artur de Magalhães, near the Avenida dos Aliados.

The building had initially been occupied by a branch of the Bank of Portugal and later by an insurance company. Derelict since the mid 90’s, the building was completely remodelled by the architect Pedro Barbosa in 2011 and returned, within possibility, to its original form with an open-space logic. The floors, windows, frames, ceilings and skylights were all recovered, along with the installation of an elevator and the demolition of more modern additions, apart from the added recessed story. This last level remained destined for habitation, while the rest was placed on the market as office space. The 2008-2011 crisis consolidated the failure of the investment.

Once the building was selected in 2015, the conception of the project was handed over to the Polish studio HiS (specializing in shop architecture, recreation and interior design), regular collaborators of Hard Rock Cafe International, having accomplished 6 projects from their portfolio. Thus, a circular chain that articulated all of the involved parties was created, with the Portuguese studio acting as a hinge, remaining in charge of the adaptation and compatibility of the project (obeying local legislative imperatives, procuring licenses, the indication of suppliers and coordinating with specialties).

The building largely maintained its original properties. The original wooden structure of the slabs was kept, being reinforced in some parts with a metallic structure due to the load increase, determined by the heavy HVAC infrastructure that a completely climatized space demands. The more profound alterations were limited to the transformation of the central staircase into a service stairway, the creation of a new staircase that crosses all of the stories and the creation of an opening in the slab of the first story, allowing for a panoramic view over the stage.

III.

Hard Rock Cafe’s commercial logic is the “experience economy”, which was first theorized at the end of the 90’s 2 and defends the transformation of the relationship between the consumer and the brand through the transformation of the act of consuming through a mnemonic interaction, reaping its added value. The brand exponentially and infinitely complexifies, dilutes and expands itself as a consequence of the interactive dialogue with the consumer. “In short, we are the brand”, the memory and the product.

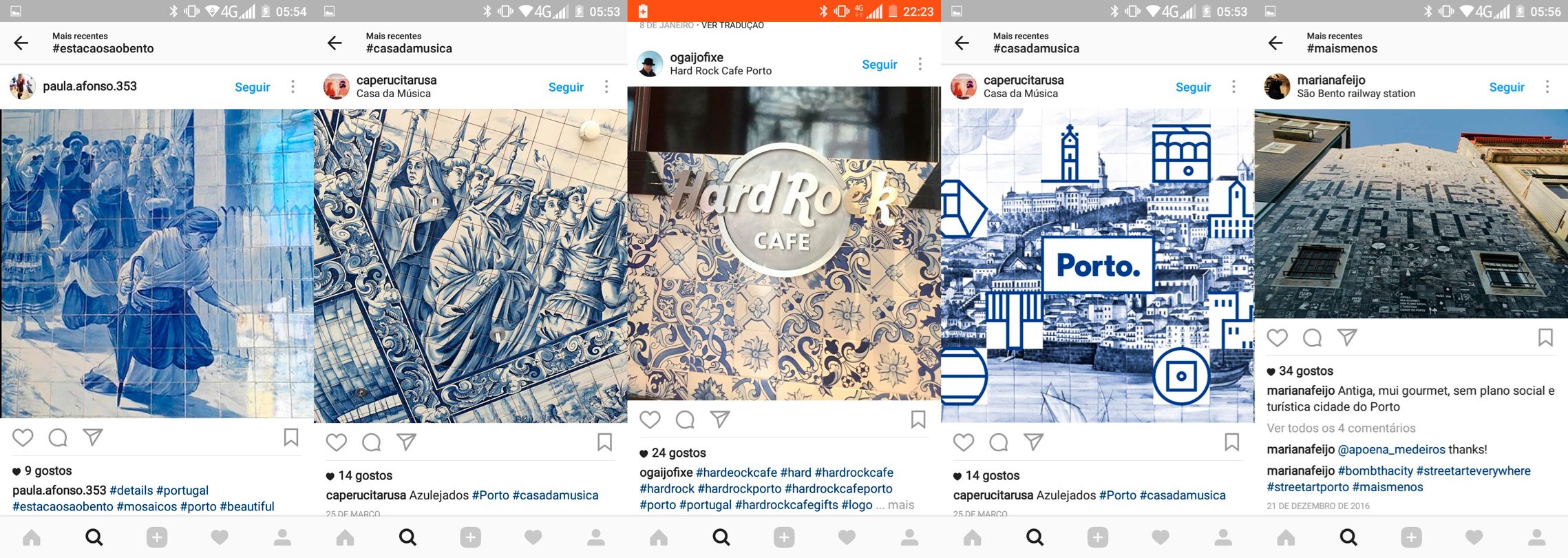

The commodification of memory, propagated by brands, is founded on intellectual devices that, according to John Urry, promote a “dissolution of boundaries, not only between high and popular culture, but also between different forms of culture, such as tourism, art, photographic education, television, music, sports, consuming and architecture” 3.

In its interaction with artistic heritage, namely architecture, this dissolution allows brands to manipulate and distort patrimonial concepts such as authenticity. For example, the constant appearance and disappearance of the “auratic” dimension is a decisive contribution to a state of anxiety, confusion and frenzy for which consuming is the only palliative. As Michael Sorkin explains, “in the era of mechanical reproduction and the death of the aura, plagiarism and theft become irrelevant and the meaning of discourse arbitrary. The value of the brand can only therefore be defended through more and more co-optation” 4. The simultaneous fascination for the exotic and the longing for the comfort of the familiar make the tourist the main consumer target of these appropriations and their subsequent devolution as staged realities. Chains such as Hard Rock, Starbucks or Planet Hollywood function as mini theme parks in the middle of a larger theme park, the tourist city 6.

As such, an attempt at an architectural critique of Porto’s Hard Rock Cafe is only possible when understanding it as a sophisticated “experience economy” machine. Only in the context of this paradigm is it possible to understand some of the apparent paradoxes of the project. One example is the apparent contradiction between the effort of completely maintaining the decorated ceilings and the carefree placing of the lighting. Another example is the somewhat forced and exaggerated introduction of the ceramic cladding (imitating Portuguese tile) to underline the character of a local building, which by default is already authentic. Other examples are the visual noise caused by the screen-printed doors, the profusion of television screens and perhaps the excessive variety of exuberant decoration that obfuscates the views over the city.

Paradoxically, with each design inconsistency, each decorative incoherence, each conflicting instance between the old and the new, the “machine” seems to work better, allowing the “product” and the “placement” to reinforce each other. This association between brand and architecture seems to represent, as Sorkin notes, “the door to the resuscitation of style as a category of evaluation” 7. The arbitrariness of this style can only be judged by another component of the brand system, celebrity 8. And there is no shortage of celebrities or relics of celebrities at the Hard Rock Cafe, they can be found on every wall.

In Porto’s Hard Rock Cafe, the only historical weight of the building that seems to survive is the outer shell. The disappearance of the of the old materiality, solid and real, engulfed by a new materiality, evasive and simulated, reminds us, much like the remodelling by Rem Koolhaas of the Illinois Institute of Technology 9, of the growth of a “new type of architecture for a world where the material and the historical no longer guarantee authenticity or meaning” 10. Faced with the impossibility of contradicting this phenomenon, it remains for architects to safeguard as much reversibility as possible, an aspect in which Porto’s Hard Rock Cafe is exemplary.

Yet this vacuity of meaning and absence of materiality doesn’t only affect architecture, it also contaminates the city and explains, in good measure, the expansion and attraction of brand culture. In fact, this end up “introducing a certain order and coherence in the multiform reality that surrounds us” 11 because “the cultural power to create an image, to define a vision of a city has become more important, as (…) traditional institutions – whether social classes or political parties – have become less relevant mechanisms for the expression of identity” 12. As such, in the absence of the politics of the polis, the city and architecture find themselves at the mercy of private aesthetic projects by large corporations that force us to, as Anna Klingmann explains, “(…) look at cities not as an urban silhouette, ´skyline’, but as a landscape of brands, ‘brandscape’, and at buildings not as objects but as advertisements and tourist destinations” 13. Alas, it is this admirable new vision of the city and heritage, modelled by the processes of aestheticization and the simplification of language imposed by brands, that explains the desire to reduce the virtual space of the city to a slogan, a logo or a brand 14 - “I ♥ NY”, “I AMsterdam”, “PORTO.” – consequently also reducing the space for its criticism.

“In the end, what makes advertising so superior to criticism? Not what the red neon sign says – but the scorching reflection of the puddle in the asphalt”. 15 ◊

Bibliography

BENJAMIN, Walter, “This Space for Rent” in “One-Way Street, Selected Writings, Volume 1: 1913-1926”, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1996.

BETSKY, Aaron, “La arquitectura del control de costes”, A+T “Nueva Materialidad I “, issue 23, A+T ediciones, 2004.

CEREJO, José António, “Dez anos de confusões e suspeitas” in Público, 21 February 2006.

EVANS, Graeme, “Hard-Branding the Cultural City – From Prado to Prada”, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, Volume 27.2, 2003.

GIACHETTI, Daniel, “Hard Rock Café e marketing; il binómio di un sucesso mondiale”, Facolta Di Economia, Rimini, 2012.

LUSA, agência, “Primeiro restaurante Hard Rock Café abre em junho em Lisboa” in Público, 17 April 2003.

KLINGMANN, Anna, “Brandscapes”, MIT Press, Massachusetts, 2007.

KOOLHAAS, Rem, “Delirious No More”, Wired Magazine, 6 January 2003.

PINE II, Joseph, GILMORE, James H., “Welcome to the experience economy”, Harvard Business Review July-August, 1998.

SOLÀ-MORALES, Ignasi de “Património Arquitectónico ou Parque Temática”, in “Territorios”, 2003.

SORKIN, Michael, “Brandaid”, No. 17 / Design, Inc. Commodification: Collaboration and Resistance Essay.

URRY, Urry, “The Tourist Gaze”, Sage, London, 2002.